In the beginning there were points. Goals and assists were the measures of hockey players, and just like people often call a spreadsheet sterile today, people 100 years ago likely got annoyed at too much attention to the box scores. They too are sterile.

It is obvious watching a hockey game that it isn't sterile. There's so much spitting, the germs have to be rampant. And of course, the other thing that spews out everywhere is emotion. Numbers are sterile because they are facts, unencumbered by emotion. And who wants that?

Because hockey switched from just counting goals and assists and shots on goal and hits and giveaways and takeaways and faceoffs and... er, sorry. Because the NHL began counting one more thing – shots that weren't shots on goal – all hell broke loose and the very idea of what it's morally correct to think about hockey became a thing people actually talked about. Loudly.

The nerds made it sterile and took all the emotion out of the game. Completely. They stripped out all the feeling, the rage, the hatred, the violence, the anger, the blood, the fists, er, sorry again. I suppose the nerd-haters cared about love and joy and other things that are more difficult to express than hate, but they would never say so unless they'd had a few beers with the boys. It was hate, hate all around in a very tedious argument that maps almost perfectly onto every culture war topic tedious-ing up the internet more than a decade later.

When I was young, people measured themselves and proclaimed their value as people by Blue or Canadian. And I don't mean Leafs or Habs, though it's no accident that they could be confused for one another. Nothing here is new.

People today are impatient, and they don't wait for advertisers to tell them what to use as tribal markers; they get together and make up their own. And one way to declare tribal affiliation is with jargon. The more impenetrable the better. And so the word Corsi was coined, named after a person, but that's as useful as calling something a Watt or a Pascal. The intent wasn't to shore up the barricades, the insiders in a nascent system are too inside to even notice there are barricades at that point, but it becomes a barrier in effect. Mostly because everyone has the knowledge of all of human history in their pocket, but actually looking something up is so uncool and besides there's 10 new notifications, and OMG did you see what they said about the thing?

No one at all every typed into Google: What the hell is Corsi? Other than me, that is.

I've come around on the name because it avoids the semantic argument that I have a very firm opinion on. Shots are all shots. A shot attempt could be a term you use for when someone fans on it, but there either is or is not a shot. There is no try. Shots on Goal are a subset of shots. Blocked or unblocked shots are a subset of shots. With Corsi as a term, you don't ever have to hear me go on about this.

Corsi turned out to matter for one thing. It was a better approximation of possession than Shots on Goal. The NHL has now given us time spent in each zone via player and puck tracking. As of now, though, no one has publicly done any work to say if that measure of possession functions better than Corsi. But I know how I'd bet on that.

Knowing who has the puck more is interesting, but it's just trivia, like who skates the fastest or who has more "speed bursts". What makes it matter is that it is predictive of future results. Goals predict the future too, though. A team that has a positive goal differential is more likely to win games than one that doesn't. And to some extent, goals predict the future with some decent granularity, but they aren't good enough at it that you'd want to bet the farm on it. Or make decisions as a GM of a team based on just goals or the standings.

Corsi predicts the future better. And that's all it does. At the player level, it gives you a very imperfect idea about how well that player does overall. But here again, making some ranked list of players based on their on-ice Corsi is going to be misleading. It's a context-free number that lies to you often enough, you might as well just go by points. You can measure individual Corsi also known as personal shooting, but if you mistake more for better, you've missed something fundamental about the game.

And none of this is about effort or caring or toughness or how much a player wants it or the word that sums all that up: heart. Except of course it is. The big criticism of the sterile numbers has always been that they have no heart in them. You can just watch the game, and you will see (by which is meant feel) that one guy there, he really has heart, miles and miles of heart and that's what really matters.

Consider Bobby McMann.

I have looked upon McMann and exclaimed in joy. He has heart. So much so, he needs to go sit down for two minutes fairly often. But he isn't emoting the puck into the net. He is so much fun to watch and his story of perseverance and self-sustaining belief is really inspiring. And now I'm going to just throw all that out the window, declare it irrelevant and make it all about facts. Sterile facts.

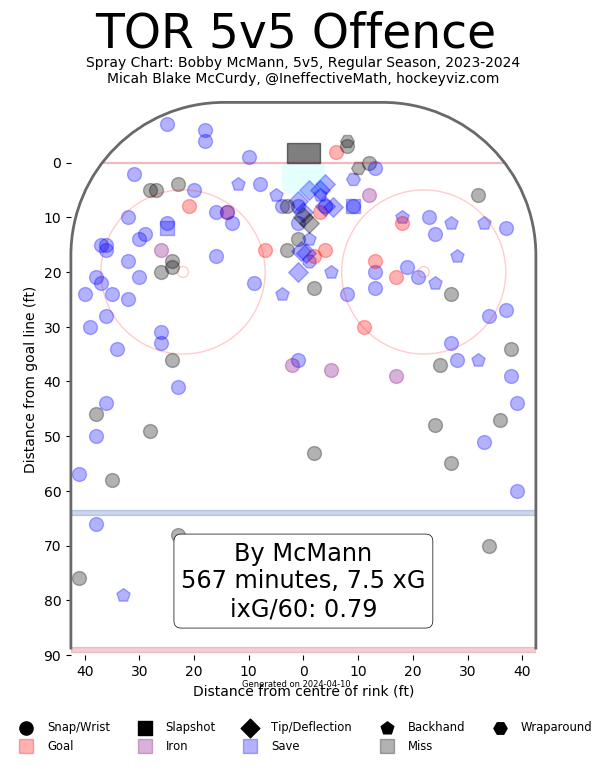

One fact is that McMann is actually better at defence than offence, even allowing for his own shooting. You likely don't really see that watching him though, because this is what you're watching for:

That is a lot of shooting. For a guy that plays in the bottom six most of the time, and who only gets 12 minutes a game (including PK time), that is a lot of shots. And .79 Expected Goals per 60 minutes on those shots is top-six territory. He's extraordinary. Possibly unique.

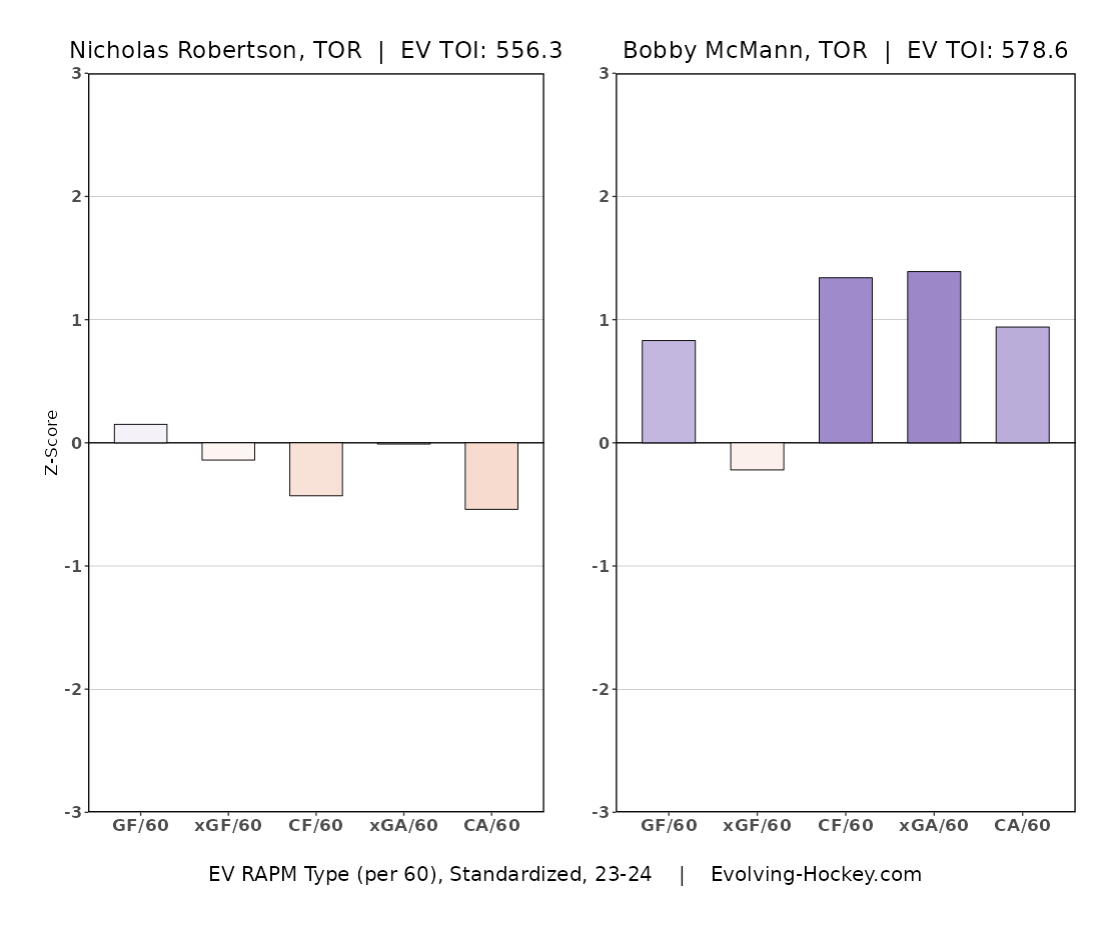

Now some more numbers at just five-on-five:

- Auston Matthews shoots (so individual Corsi or iCF) at a rate of 22.2 shots per 60 minutes.

- Bobby McMann shoots at a rate of 18.71

They are one and two on the Leafs. They are third and 22nd in the NHL for players with at least 300 minutes played this season. And I don't think you can see that watching the game with any precision, particularly not in a low-minute player. I think you have to measure that. Actually I know you can't see it because the urge to place Nick Robertson ahead of him in the lineup is felt by many, many fans who watch a lot of games.

If you don't know this stuff, McMann's goals seem to fall from the sky like amazing gifts of the gods. He's 20th in the NHL in rate of goals scored. I assume you can figure out where Matthews is on that list.

And now for the really interesting bit, er sorry, lifeless numbers. He's eighth in the NHL at the rate of unblocked shots per 60 minutes. He's getting almost everything past the defenders. Now, there's a host of possibilities of why that is – people haven't figured out what he can do, so they don't try to block his shots. He plays a lot against bottom six lines who aren't expecting a shooter opposite them. Randomness is everywhere in all these numbers. Pick a story to explain it, and reveal your biases.

His shooting percentage on those unblocked shots is down the list quite a bit, 116th. He is shooting a lot, not getting blocked and shooting from very good locations most of the time. That recipe is getting him goals, and it will continue to. His talent as a shooter is less of a factor and that might be why he seemed to languish in obscurity. Sick hands get you drafted, dealing in volume doesn't.

What is it about McMann that gives him this game? This very unusual style of play, where he doesn't have any meaningfully positive impact on his forward linemates (he has no negative either), where he is actually good defensively, which is likely what got him called up in the first place, but he shoots all the time and he shoots smart.

Well, it's heart, isn't it? That's what it is about McMann that lets him do all these things. He has to believe he can before he does it.

Back in the day, "don't tell me about heart" wasn't just an excellent username, it was the battleground with the people who just didn't want to count that one extra thing. They wanted to watch and tell stories about heart or the lack of it. They wanted to declare certain types of players devoid of all good character. One might suspect they needed to. Desire, intention, manliness and toughness mattered while the numbers were alleged to be devoid of emotion.

Which they aren't and they never were. The numbers have everything in them, heart, faceoffs, defence, offence, desire, health, happiness, focus and effort. But you can't see those things clearly. Your eyes can't count. Your mind is clouded by expectation and emotion. You can only imagine you see into the heart of a player while you make up tall tales about them. If McMann doesn't score it's because he's just complacent now, you might say, and reveal things about yourself and how you think. If a player doesn't look upset after a loss you might think that's him hiding his feelings or you might say he obviously doesn't care. Revealing yourself. If he gets a contract and also doesn't score for awhile, then the stories change again and you show who you are.

McMann the man, meanwhile, is still a mystery.

If you are watching Bobby McMann, and you don't know how much he shoots, how good his defensive impacts are, how he's leveraging volume and location to maximize his mildly good shooting talent, if you are in the dark on all of that, you can only tell stories about yourself, not McMann. He's driving the net because he's not afraid of the dirty areas! He's trying to get a playoff roster spot, so he's working harder! It's a little morality play, told by the play-by-play people, the fans to each other, the GM up in the box, the coach behind the bench, the official scorer to their assistant as they punch in shot locations. It's not really about McMann at all.

And yet. And yet. He has to believe he can be a player before he is one. The people around him have to believe. Inside his own head, it's about nothing but heart. This is true for Nick Robertson too, though. We can't measure heart, but I know how I'd bet on a contest between the two of them: dead heat. You need the spreadsheet to pick between them. The team needs something else to create a space for Robertson to find his maximum self.

In the end, there is just points. But the way we describe how they were created isn't pure fiction anymore.