When I was a young kid - I mean really young, say 8 years old - I played defence for a couple seasons. Kids at that age really don't know much about anything in the game, much less the finer points of defensive positioning, but we were always told that when defending a rush we should try to challenge an attacking player for the puck at our own blue line. There are three main reasons for this:

1) If you succeed in choking off the rush, your opponent can't gain your zone at all. The attacker's teammates won't be able to provide outlets inside your zone, and ultimately, this limits the forward movement of the puck.

2) Even if all you do is slow up the attacker, odds are good that one of his teammates will wander off-side, disorganize the attack , and/or cause a whistle.

3) If your opponent dumps the puck in, odds are good that your defence partner will have the inside step on collecting a loose puck in your zone. Communication with a wandering goalie is important here, but that's another issue.

This is not to say that a defenceman should go for a big hit at the line or do anything to put himself out of position, but ideally, he will simply angle off the forward towards the outside of the ice (gap control is important, here) and either sweep the puck away with a poke check or make contact along the boards. In terms of defensive responsibility, the safest form of contact is to "rub someone out" while skating in the same direction as them. That way, if you miss, you're not way out of position. Lunging at someone going the opposite direction sure inflicts more pain, but also takes you out of a play, whether or not you miss.

Refusing to give up your own blue line, as far as I can tell, has been a nearly-axiomatic philosophy to playing defence anywhere I've ever played, watched, or coached hockey. So why does it seem like the Leafs give it up a lot? Maybe we can find some kind of pattern, here.

Sure, sometimes the Leafs do challenge

Either due to an engrained habit or due to Carlyle's expectations (I guess we don't know), the Leafs' defenders are happy to challenge a rushing opponent at their own blue line from time to time. Here, Cody Franson is about to pinch off an Oiler. Nazem Kadri has fallen back wonderfully to take the place of a rushing Morgan Rielly who, bless him, has used his wheels to get almost all the way back already, anyway. There really is only one rushing forward who doesn't have a lot of options, and so the carry-in is maybe a strange thing to attempt here, but whatever.

Franson puts himself out a bit to make a hit, and though he doesn't get all of the attacker, he dislodges the puck, and Kadri, being a good boy, collects the loose puck, throws a cross-ice pass behind the net to an open Rielly and the Leafs start out the other way. Or, at least they would have, if David Broll hadn't bungled the breakout pass he got from Rielly. Textbook work at the blue line, anyway.

Defending an odd-man rush

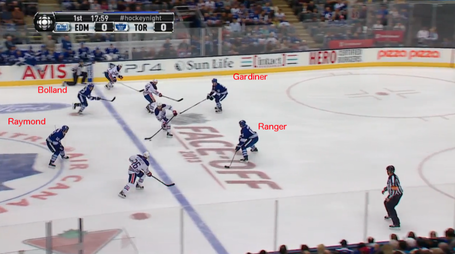

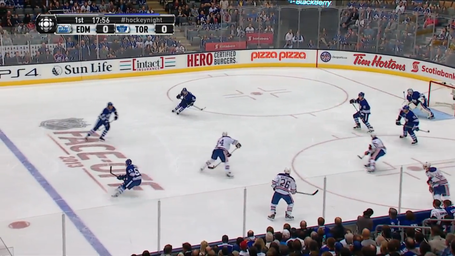

Here, we see Jake Gardiner and Paul Ranger defending what is briefly a 4-on-2. Should they back off the line in this instance? Of course. Eliminating one of the attackers is going to be an even bigger problem if his teammate picks up the puck with even more room on a 3-on-1. This play maybe looks a bit worse than it is, since Dave Bolland has just stepped off the bench and was passed by the attackers. Raymond is also on his way.

A good stick by Ranger more or less breaks up this rush and Leafs get back, but not before the Oilers regain possession and get a chance on net. The puck has taken a bit of a fluky bounce and catches the defenders deep and the forwards covering nobody. Oh well, it was an odd-man rush. Ryan Smith from there? That's an easy save for Bernier.

The Leafs ran around in their own zone for a while after this, but that's getting away from the point of this article.

But it's not always an odd-man rush

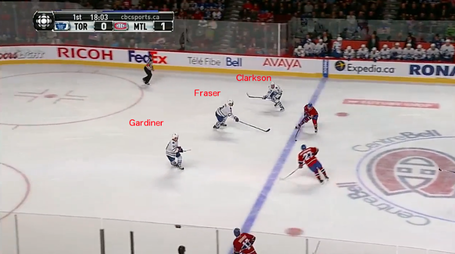

Here is an instance in another game where the Leafs' D clearly have numbers but continue to back off. The Habs carry this puck right over the blue line and the D wait until the puck carrier has shot the puck (just above the top of the near side circle) before challenging. You might argue that the Hab on the weak side forces the D to back off for fear of being out-flanked, but that should only force Gardiner back a couple steps. Clarkson could conceivably be applying backside pressure and Fraser could easily have stepped up. Why not?

As it happened, the filthy Hab got a shot away, though Mark Fraser's stick deflected the puck into the near corner. The Leafs exited the zone shortly thereafter, and so no damage was done. The thing is, controlled entries are something you generally want to avoid, regardless of the outcome of this specific example.

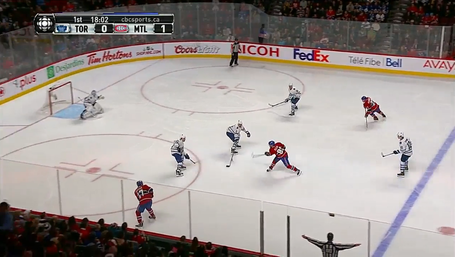

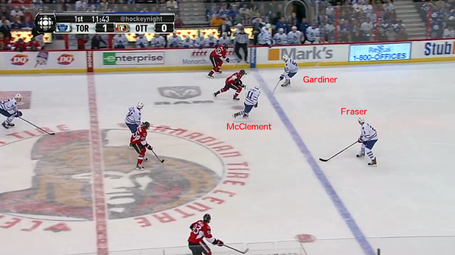

Let's look at another example from a different game. Here, Jason Spezza is carrying the puck along the far wall, and the Leafs have great support, and they certainly have numbers. Why is Spezza permitted to cross the line? Well, Gardiner is probably worried that Spezza will pass off to the guy that McClement isn't really covering.

Spezza throws on the brakes as soon as he crosses the line and his linemates go deep. He throws the puck into the slot to Mika Zibanejad and the puck deflects out of play off a Mark Fraser stick. The immediate threat is gone, but the point remains that the Sens gained the zone easily, and now get an offensive zone draw.

So why is this happening?

Am I the only person to observe the Leafs backing off their own blue line more than they should? Do the defencemen lack confidence in their own abilities or those of their peers? Is it a question of gap control? Offensive zone turnovers? My sense of things is that it's a combination of all three, but as far as I know, challenging for the puck at your own blue line (while defending a rush) is such a basic part of defending that I can't understand why it's not happening.